List 30 things that make you happy.

The letter had arrived with the morning post, its formal seal and academic parchment marking it as correspondence from the Lumenvale Institute of Philosophical Studies. Master Cornelius Brightquill had requested—with the polite insistence that scholarly institutions wielded like finely crafted weapons—that I contribute to their upcoming symposium on “The Nature of Human Contentment.”

*”Honored Scribe Aldwin,”* the letter read in perfect calligraphy, *”we would be delighted if you would prepare a presentation on personal happiness. Specifically, we request that you compile a list of thirty things that bring you joy, to be analyzed alongside similar submissions from citizens across all walks of life. Your reputation as both storyteller and keen observer of human nature makes your perspective invaluable to our research.”*

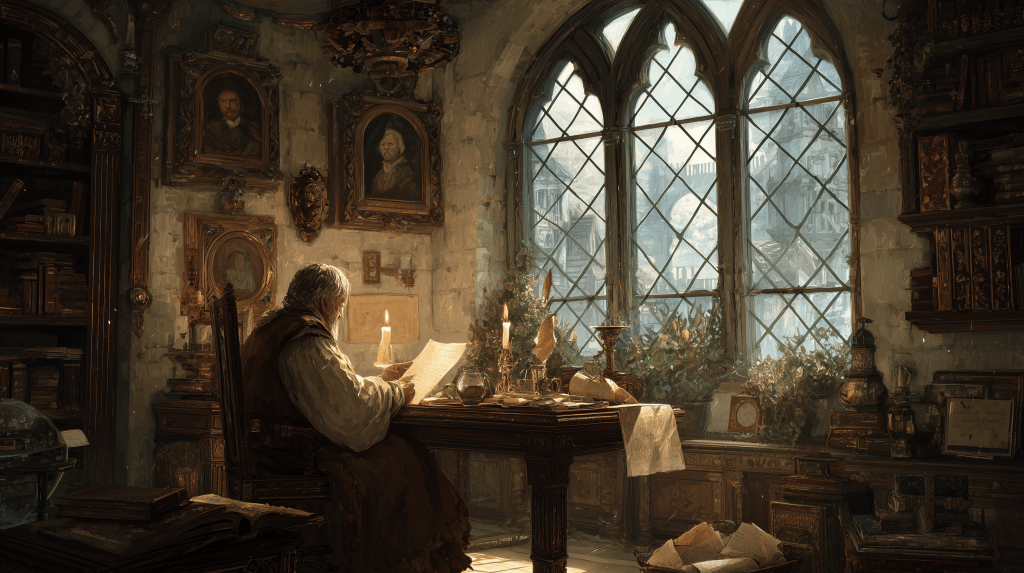

I set the letter aside and leaned back in my writing chair, watching dust motes dance in the afternoon sunlight that streamed through my study windows. Outside, the familiar sounds of Lumenvale’s Scribes’ Quarter provided their usual symphony—the scratch of quills on parchment, the soft thud of books being shelved, the murmured conversations of scholars debating points of arcane significance that would change no lives but occupied their minds completely.

Thirty things that make me happy.

The request should have been simple. After forty-three years of living, twenty-two years of marriage to my beloved Rosella, and fifteen years of watching our twin daughters grow from squalling infants into young women who could make me laugh until my sides ached—after all those years of accumulated experience, surely I could identify thirty sources of joy.

Instead, I found myself staring at a blank sheet of parchment, my quill poised over the ivory surface like a hunter’s arrow aimed at prey that refused to hold still long enough for a clean shot.

The Academy scholars would expect complexity. They thrived on intricate analyses of emotion, on theories that required three-volume treatises to explain properly. They would want to hear about the subtle pleasures of intellectual discourse, the aesthetic satisfaction derived from observing the Crystal Spires’ daily light-dance, the philosophical contentment that came from understanding one’s place in the grand tapestry of existence.

But as I sat there, honestly examining the contents of my heart, I realized something that would probably disappoint the learned masters: my happiness was embarrassingly simple.

I rose from my desk and moved to the window, where I could see the cobblestone street that led toward our modest home in the Quarter of Small Delights. Rosella would be preparing the evening meal about now, her movements around our kitchen carrying the practiced grace of someone who had learned to transform humble ingredients into sustenance that nourished more than mere bodies. The twins would be returning from their apprenticeships—Lydia from the Healers’ Hall, Elena from the Academy’s junior scribal program—both of them eager to share the day’s small victories and minor disasters with parents who had learned to find fascination in every detail of their daughters’ evolving lives.

That right there. That anticipation of their voices filling our home’s warm spaces, of Rosella’s smile when I walked through the door, of the four of us gathered around our worn oak table sharing food and stories and the comfortable silences that marked a family who genuinely enjoyed each other’s company—that was my first source of joy.

Time with them. Just… time.

Not structured time or quality time or any of the elaborate phrases that the relationship counselors in the Healers’ Quarter used to describe proper family dynamics. Simple presence. Being in the same space, breathing the same air, existing as part of something larger than individual concerns.

I could spend an entire evening doing nothing more than listening to Elena practice her storytelling techniques, watching the way her hands moved as she shaped narratives out of raw imagination. Or sitting beside Rosella in our small garden while she tended her herbs, not talking about anything important, just sharing the peace that came from compatible silence. Or walking with Lydia through the morning markets, her healer’s training making her notice details about people’s health and happiness that never would have occurred to me.

That was happiness. Not thirty different variations of contentment, but one profound source of joy that could fill a lifetime without ever growing stale.

My second source of happiness lived in the ritual we had developed over the years of taking our evening meals at the Copper Chalice every sevenday. Nothing fancy—the tavern’s cooking was solid rather than inspired, and the atmosphere leaned more toward comfortable than elegant. But there was something magical about those evenings when the four of us claimed our favorite corner table and spent two unhurried hours talking about everything and nothing.

The twins would share stories from their respective training programs, their descriptions of patients healed and manuscripts copied bringing distant corners of Lumenvale’s community into our intimate circle. Rosella would recount the social dynamics of her weaving guild, painting verbal portraits of her fellow artisans that revealed both her sharp observational skills and her fundamental kindness toward human foibles. And I would contribute tales gathered from my clients—carefully anonymized, of course—about the hopes and fears that drove people to commission stories for loved ones.

But the real magic wasn’t in the stories themselves. It was in the way we lingered over our meals, in how time seemed to slow down when we were together like that, in the particular quality of laughter that emerged when four people who truly knew each other discovered something worth sharing. The tavern’s honey-glazed bread became a feast when eaten in such company, and their simple barley soup tasted like ambrosia when seasoned with genuine affection.

Good food, yes, but made transcendent by good company. That was my second joy.

The third source of happiness would probably sound peculiar to the academic minds requesting this analysis. Three times a year, I borrowed Keiran’s wind-steed—a magnificent creature of air and starlight that could cover ground faster than thought itself—and spent a day riding the thermal currents above the Whispering Woods.

The scholars would expect me to wax philosophical about communing with nature or finding perspective through elevation. They would want to hear about spiritual enlightenment achieved through solitary contemplation at altitude.

The truth was simpler and more visceral: I loved the speed. The way the world blurred beneath us when the wind-steed caught a strong thermal and shot skyward like an arrow released from a master archer’s bow. The way my heart hammered against my ribs when we dove through cloud-banks, moisture streaming past us in silver ribbons. The pure, uncomplicated exhilaration of moving faster than earthbound creatures were meant to travel, of surrendering control to something magnificent and wild and gloriously alive.

Those rides left me wind-burned and grinning, my hair tangled and my formal scribe’s robes thoroughly inappropriate for the undignified whooping I invariably produced when the steed executed particularly dramatic maneuvers. But I returned home feeling somehow recharged, as if the speed had burned away accumulated worries and left behind only the essential core of who I was beneath all the social expectations and professional responsibilities.

Fast and loud and utterly without practical purpose—except for the way it made me feel completely, unreservedly alive.

My fourth joy was why I had become a scribe in the first place, though it had taken me years to understand the deeper reason behind my career choice. I loved creating stories. Not just transcribing them for clients or copying manuscripts for the Academy’s archives, but the actual process of reaching into the realm of possibility and pulling back something that had never existed before.

Late at night, when the house was quiet and my family safely asleep, I would light a single candle and let my imagination run free across empty parchment. Sometimes the stories were grand adventures featuring heroes who possessed courage I could only dream of claiming. Sometimes they were quiet domestic tales about ordinary people finding extraordinary meaning in everyday moments. Sometimes they were pure flights of fancy involving talking animals and sentient mountains and magic that operated according to laws I invented as I wrote.

The satisfaction that came from crafting the perfect sentence, from finding exactly the right word to capture a character’s emotional state, from building narrative tension that released in moments of genuine surprise—nothing in my professional life compared to those solitary hours of creation. When a story was working, when the characters felt real enough to argue with me about their choices and the plot developed momentum beyond my conscious control, I experienced a state of focused joy that made time irrelevant.

Writing stories was my conversation with the infinite, my way of adding something meaningful to the vast library of human experience. Each tale I created became a small contribution to the great project of understanding what it meant to be alive, to struggle and love and hope and fear in a world that offered both beauty and sorrow in equal measure.

And that was it. Four sources of happiness, not thirty.

Time with my family, sharing meals together, the exhilaration of speed, and the satisfaction of creating stories that might outlive their creator. Simple things, really. Embarrassingly simple, perhaps, for someone expected to provide scholarly insight into the nature of contentment.

But as I finally set quill to parchment and began my response to Master Brightquill’s request, I realized that simplicity might itself be a form of wisdom. Perhaps the scholars would learn something valuable from discovering that happiness didn’t require an elaborate catalog of pleasures, that contentment could be built from just a few foundational joys pursued with genuine appreciation.

*”Honored Master Brightquill,”* I wrote, *”I find myself unable to compile the requested list of thirty things that make me happy, for the simple reason that my happiness springs from only a few sources, each so profound and complete that pursuing additional pleasures seems unnecessary.”*

*”Instead, allow me to offer this observation: True joy may not be found in the accumulation of many small satisfactions, but in the deep appreciation of a few great ones. A man who truly cherishes his family’s company, who finds transcendence in shared meals, who occasionally surrenders to the intoxication of speed, and who creates stories that capture some small truth about the human condition—such a man may discover that four joys are more than sufficient for a lifetime of contentment.”*

*”Perhaps the question is not how many things can make us happy, but whether we are wise enough to recognize when we already possess everything necessary for joy.”*

Outside my window, the afternoon light was beginning its transformation toward evening gold. Soon, I would close my ledgers, bank the fire in my study, and walk the familiar streets toward home. Rosella would smile when I entered our kitchen, the twins would greet me with stories from their day, and we would share another evening of the simple, profound happiness that had sustained me for decades.

Thirty things that make me happy?

No.

Four things that make me completely, unreservedly, abundantly happy.

And that, I thought as I sealed my letter to the Institute, was more than enough for any man to ask from life.

Leave a comment