What is a word you feel that too many people use?

Master Scribe Veridan Ashworth set down his silver-nibbed editing quill with the deliberate precision of someone exercising extraordinary restraint. The manuscript before him—the seventh he had reviewed this morning for the Lumenvale Literary Guild—bore all the hallmarks of what he had come to recognize as “aspirational mediocrity.” Competent prose wrapped around predictable phrases that revealed a fundamental lack of imaginative courage.

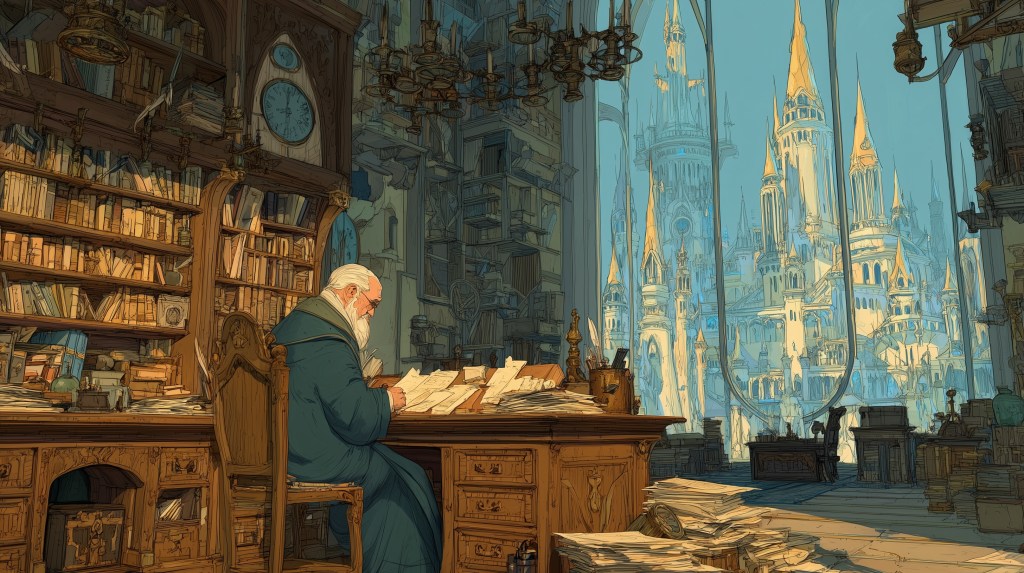

His study overlooked the cobblestone courtyard of the Guild’s publishing house, where morning light filtered through crystalline windows to cast prismatic patterns across the worn oak of his editing desk. Twenty-three years of manuscript evaluation had taught him to recognize promise within the first three paragraphs, just as they had taught him to identify the linguistic shortcuts that marked lazy thinking disguised as literary effort.

“Another ‘against all odds’ protagonist, I presume?”

Veridan glanced up to find his colleague, Master Editor Lydia Thornwick, standing in his doorway with an expression of weary amusement. Her silver-streaked hair was gathered in the practical bun she favored during particularly demanding editorial sessions, and ink stains decorated her fingers like badges of professional dedication.

“Worse,” Veridan replied, gesturing toward the offending manuscript. “This young author has managed to combine ‘against all odds’ with ‘little did they know’ and—” he paused for emphasis “—’you couldn’t make this stuff up,’ all within the first chapter.”

Lydia winced visibly. “That last one particularly grates, doesn’t it? Of course someone made it up. The author made it up. That’s literally what fiction means.”

“Precisely!” Veridan’s voice carried the passionate frustration of someone whose life’s work involved elevating language rather than watching it deteriorate into convenient clichés. “It’s a phrase that pretends to authenticate the remarkable while simultaneously acknowledging its fictional nature. The logical contradiction alone should make any thinking writer pause.”

He stood and began pacing the narrow confines of his study, a habit that emerged whenever he encountered particularly egregious examples of literary carelessness. The walls around him bore the accumulated weight of thousands of manuscripts—some brilliant, many adequate, too many populated with the same tired expressions that had been drained of meaning through repetitive use.

“What troubles me most,” Veridan continued, warming to a subject that had increasingly occupied his thoughts, “is how these phrases function as barriers to genuine expression. When a writer reaches for ‘you couldn’t make this stuff up,’ they’re essentially admitting defeat—acknowledging that they lack the skill to make their fictional events feel authentically remarkable through the quality of their storytelling alone.”

Lydia entered the study fully, settling into the leather chair reserved for extended editorial discussions. “You’ve been thinking about this quite extensively, haven’t you?”

“How could I not?” Veridan gestured toward the stacks of manuscripts that surrounded them. “Every submission brings fresh evidence of linguistic entropy. Writers who substitute familiar phrases for original thought, readers who apparently find comfort in predictable expression rather than challenging themselves with language that might genuinely surprise them.”

He returned to his desk, picking up the manuscript to read aloud: “‘Marcus couldn’t believe his luck. Against all odds, he had discovered the ancient tome that scholars claimed didn’t exist. Little did he know that his greatest adventure was about to begin. Truly, you couldn’t make this stuff up.’”

The words hung in the air between them, their lack of originality somehow made more apparent through vocal delivery.

“The author used four separate clichés to establish basic narrative premises,” Veridan observed. “Rather than trusting their ability to create genuine surprise or wonder, they’ve essentially apologized in advance for asking readers to engage with fictional events by reassuring them that similar expressions have been accepted before.”

Lydia nodded thoughtfully. “It’s become a form of linguistic comfort food, hasn’t it? Phrases that ask nothing of either writer or reader—familiar sounds that create the illusion of communication without the risk of actual expression.”

“Exactly.” Veridan sat back in his chair, feeling the familiar weight of professional responsibility settling across his shoulders. “Which is why our role becomes increasingly important. We’re not merely evaluating technical competence anymore—we’re serving as guardians against the gradual erosion of language itself.”

Through the study windows, Lumenvale’s Crystal Spires caught the midday sun, their surfaces refracting light into countless unique patterns that no two observers would perceive identically. Veridan often drew inspiration from their ever-changing display, using it as a reminder that beauty emerged from specificity rather than generic approximation.

“What would you say to young Marcus’s author?” Lydia asked, gesturing toward the manuscript.

Veridan considered the question seriously. His editorial letters were renowned throughout the literary community for their combination of honest assessment and constructive guidance—responses that challenged writers to exceed their current capabilities while providing specific pathways toward improvement.

“I would tell them that every tired phrase represents a missed opportunity,” he said finally. “That ‘you couldn’t make this stuff up’ should actually serve as a challenge rather than a disclaimer—an invitation to make their fictional events so compelling, so beautifully rendered, that readers forget they’re engaging with imagination rather than documented reality.”

He pulled a fresh sheet of parchment toward him, dipping his quill in the enchanted ink that would ensure his words reached their intended recipient with clarity and permanence.

“I would explain that the most effective fiction doesn’t ask readers to suspend disbelief so much as it makes disbelief irrelevant through the sheer power of skillful storytelling. When an author truly succeeds, readers don’t think about whether events could have been ‘made up’—they’re too absorbed in experiencing the story to question its origins.”

As Veridan began composing his editorial response, he felt the familiar satisfaction that came from transforming frustration into constructive action. Each manuscript represented an opportunity to elevate literary standards, to encourage writers toward greater precision and originality.

“The irony,” he murmured as he wrote, “is that exceptional fiction makes everything seem both completely believable and utterly impossible simultaneously. The best authors don’t need to tell us we couldn’t make this stuff up—they make us grateful that someone did.”

Outside, Lumenvale continued its daily rhythm of commerce and creativity, a city where language mattered because words shaped reality as surely as magic shaped matter. In his study above the literary district, Master Scribe Veridan Ashworth wielded his editing quill like a precision instrument, carving away linguistic laziness to reveal the sharper expressions that waited beneath.

The manuscript before him still required extensive revision, but within its pages he glimpsed the potential for something genuinely surprising—prose that would trust readers enough to offer them language they had never encountered before, ideas they couldn’t have anticipated, and the rare pleasure of discovering that someone had indeed made this stuff up, and done so brilliantly.

Leave a comment